A little more than five years ago, when I finally found the fabric I had been searching for for twenty years, I also found the tailor who 'matched' it, thanks to a tip from a friend. Although already retired, this master took up needle and thread for me once again and conjured up a frock coat from the wifling that I really adore

It is not only the frock coat whose perfect execution impresses me. It is the person of the master tailor who has fascinated me ever since. On the one hand, because he is the representative of a profession that is dying out. On the other hand, if Hubert Eichler were a medal, his back would also shine brightly and brilliantly. Which is not what you want to assume when you meet him for the first time: He was a folk actor of the first order. But one thing after the other.

WIFLING - THE TWEED OF TYROL

As a regional developer in the Ötztal, I had heard time and again about a legendary fabric whose lifespan supposedly stretched from the cradle to the grave. Wifling was the name of this fabric, whose 'warp' was made of linen, the 'weft' of sheep's wool. Then it took more than fifteen years until I actually discovered the fabric on a tip from my Stubai friend Detlev Klose. He took me to Neustift to Martin Stern, one of the last great handloom masters of the Stubai. On his old handloom, Michael had 'revived' this thick, robust fabric, once worn mainly in the Tyrolean side valleys. He had a not everyday white Wifling in stock. It had been left over from an order. Normally a Wifling is brown.

You should see it: My frock coat is 'Made in Tyrol', the eagle stands out elegantly against the white wifling.

Now I just had to find a tailor who could also process this rustic cloth. I had imagined a frock coat, because one treats oneself nothing else. Here, too, the tip came from a friend. He referred me to the master tailor Hubert Eichler in Sistrans. He was already retired, but if I begged him long enough he might be persuaded, they said.

THE TAILOR WITH THE MISCHIEVOUS IN HIS EYES

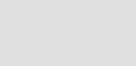

When I knocked on the door of the former tailor's workshop, a rather small, wiry man opened the door to me, and you could hardly tell that he was approaching 80. Already at the first meeting I noticed the mischievousness in his eyes. He was working on an old Pfaff sewing machine, the iron was on. So still active in the business after all? "I still tailor for my family," he said. The fabric I had with me, however, interested him very much. Not least because of that, I managed to persuade the master. He agreed to make me a frock coat out of the fabric.

During the first fitting, we got to talking. Hubert told me about his masterful career. And to my great surprise, he also told me that he had once been an actor with heart and soul. The Volksbühne Blaas in Maria-Theresien-Straße became his passion. That, in turn, I still knew from my student days.

"My father was a tailor," he began to tell. "And after the Second World War I got an apprenticeship straight out of school. Not with my father but with a 'Boehm', the master tailor Ondratschek on Wilhelm Greil Street." He worked in the tailor's studio together with 20 other journeymen and a gaggle of apprentices. You have to imagine that. How do you pack so many tailors into a rather small space? Quite simply, they do their work sitting cross-legged on the table. That was his preferred working posture even after he took over his father's tailoring workshop.

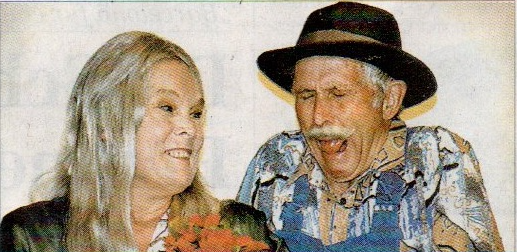

He completed his three years as a journeyman with distinction, as Ulli, Hubert's wife, adds. She had met her husband in his father's workshop. At that time, in the year 1957, his father still employed a total of 10 people. And when he returned to the tailor's shop from his military service, another girl had been employed as an apprentice in the meantime. "Ulli then captured me here," Hubert laughs in his likeable, mischievous way. A process that he had to portray again and again on stage a few years later in his 'second profession': the aberrations and confusions of love.

What can no longer be undoubtedly clarified during my visit to the Eichler couple: Who had 'captured' whom? Because that's what they called not so long ago what is meant today by 'picking up'. My suspicion: Ulli was the one who had prevailed against strong competition from her female fellow apprentices. "They all made eyes at him," she hastens to point out. And all this despite the fact that she didn't want a tailor for a husband. In the end, she 'won' the competition for the heart of the master tailor who had been tested in the meantime. As collateral damage, one of her co-workers even quit her job with Hubert's father because her efforts were in vain.

Who had 'captured' whom remains in the dark. Ulli and Hubert Eichler in front of their house in Sistrans.

Together they worked as a tailor duo, he was responsible for suits, coats and costumes, his wife for the dresses. Their customers included dignitaries, especially from Innsbruck. They had also worked for innkeepers, both remarked with audible sighs. Was there perhaps something wrong? "They used to be the worst payers," Ulli Eichler recalls. "You had to go to some inns in person up to three times to get the money. That was a pain in the ass."

In the early 80s, a new phase of life began for Hubert Eichler in two ways. Custom tailoring was all but supplanted by ready-to-wear. He and his wife worked more and more for quality-conscious regular customers. And so one day he also had the time to get involved in the Sistrans carnival. Ulli tailored him a woman's garment, in which he made an appearance that had the audience bending over with laughter.

"We all didn't know he could be so funny," says Ulli today. A 'talent scout' from the Sistrans theatre group was of the same opinion and didn't miss the opportunity to hire the master tailor for two performances without further ado: 'Geierwally' and 'Der verkaufte Großvater'. This was the springboard for higher orders: he became a member of the ensemble of the Volksbühne Blaas in Innsbruck's Maria-Theresien-Straße and remained so until 2005.

They were the 'dream duo' of the Volksbühne Blaas: Hubert Eichler and Evelyn Esterhammer. Here in the comedy: 'Der Saisongockel'.

"I learned the lines for my roles mostly while walking, and partly while working." He always found it easy to do so. On average, there were six performances at the Volksbühne im Breinössl per year whose text he had to learn. And then there was the daily rehearsal work. "He was always on the road," complains Ulli, who also had to look after the three children Hubert, Claudia and Sonja. Only Monday was free of theatre.

He loved to portray farmhands, smallholders, peasants, innkeepers and once even an Italian. He still remembers some of the titles of peasant tales with pleasure. 'Kein Auskommen mit dem Einkommen', 'Die Sache mit dem Feigenblatt' or 'Die Lügenglocke'. But his repertoire also included contemporary, 'serious' plays such as 'Siberia' by Felix Mitterer or 'Maria und Josef' by Peter Turrini.

THE REAL AND THE FAKE BARON

Hubert still fondly remembers a real baron who had once attended one of his performances. Hubert played a cobbler who disguised himself as a baron. "The next day this real Baron sought me out, got the address and paid me a visit at the workshop. He congratulated me for an excellent portrayal of a baron," the 'fake baron' still laughs today. And because he had given the role so excellently, the real Baron also immediately became a customer of the workshop

Hubert Eichler has remained like that, even today at the age of eighty-three: friendly, respectful and above all noble. A tailor as a baron.

Rate this article

Show me the location on the map

A volunteer at the "Schule der Alm" alpine farming school, cultural pilgrim, Tyrol aficionado and Innsbruck fan.

Similar articles

"If the bee disappears from the earth, humans will only have four years to live. No more…

The first time I met Isobel Cope, I was halfway through presenting my radio show Sensations in…

Click. A privacy policy like this is accepted in no time at all. Click. And the computer…

Peruvian-born Sandra Chamochumbi Castro is a member of the Limonada Dance Company, newly founded…